By Kim Bellard, February 28, 2013

There’s an old joke about the difference between bacon and eggs: the chicken is involved, but the pig is committed. Perhaps the problem in health care is that when it comes to being engaged in our own health, most of us are chicken. Maybe the wrong people have been cooking.

Patient engagement -- along with its many synonyms, such as shared decision-making or consumer-directed care – continues to be a favorite strategy for many health pundits. I am biased towards it myself, although exactly what it means, or will mean in the future, is not entirely clear.

The prestigious journal Health Affairs recently devoted an entire issue to the topic. In one study, Judith Hibbert and colleagues reported that patient activation scores help predict costs: lower activation levels were tied to higher costs, even after adjusting for risk. A separate study, also by Hibbert, reviewed the literature and concluded that patients with higher activation levels had better health outcomes and care experiences, although the evidence was more inconclusive about the effect on costs.

The trick, of course, is how to “activate” patients – is it all self-motivation, or can providers and other third parties (such as employers) encourage it?

One common method to influence patient engagement is an employer wellness program. A recent National Business Group on Health survey reports that almost 90% of employers offer wellness-based incentives, spending an average of over $500 per employee on the programs. Employers are getting tough too: 15% directly tie health plan eligibility to a health activity such as taking a risk assessment or biometric screening. Almost two-thirds already tie employee contributions to completing such activities. And 41% include, or plan to include, outcomes-based measures (e.g., lowering blood pressure) as part of the program.

Another strategy employers are using is increased employee cost-sharing, such as in consumer-directed health plans (CDHPs). Critics accuse them of simply shifting costs to employees, but there are plenty of studies that indicate they may actually change employee behavior and help control costs. For example, Cigna recently claimed that their CDHP members improved their health risk profile 12% while their health cost trend was 13% lower than traditional members. Cigna CDHP members were also more likely to take health risk assessments, to use cost and quality tools, to choose generic drugs, and to seek preventive care.

Consumers may be starting to take cost into account, but they don’t like it. A study by Sommers, et. alia, reported on focus groups of insured patients. The focus groups indicated that patients don’t like cost considerations to be part of health care decisions, and revealed that several stereotypes remain all-too-common, including that more expensive care is better care, and choosing more expensive care is some sort of victory over insurance companies (not realizing that, in the end, they and other insureds pay for that care). Patients still don’t really know how to weigh risk versus cost.

We treat health care costs much like we treat the deficit: costs come from other people, cuts should come from other people, other people should pay, and, oh-by-the-way, let’s think about it tomorrow. That has to change.

One thing that offers new hope for patient engagement is that the options for it have never been broader or more robust – mobile, electronic records, telemedicine, and social media, to name a few.

There are estimated 40,000 mobile health apps. It seems you can get an app to do just about anything you can think of, plus many things you probably hadn’t. The health apps vary widely not only in purpose but also in audience and quality. A company called Happtique has just introduced a certification for health apps that will hopefully give consumers a better comfort about which apps to use, or for physicians to know which to recommend to patients. They see the program not as a rating mechanism but as kind of like a Good Housekeeping seal of approval, assuring that at least a set of minimum standards have been met. This could spur adoption.

It does appear that physicians are joining the mobile revolution, according to CompTIA. Their recent survey indicated that one in five physicians is using a medical or health-related app daily, and 62% expect to be regular users with a year. The trick will be how they incorporate them into their practice, for patient care and/or patient engagement.

EHR/PHRs provide yet another option to engage consumers. To date, consumer adoption of PHRs have been disappointing, to say the least – even when they are available. A recent study by Ritu Agarwal and colleagues, aptly titled “If We Offer it, Will They Accept?”, explores this issue and concludes that use depends on a number of factors – not just existing consumer preferences but also satisfaction with the patient-provider relationship, provider support for patient use of the PHR, and specific communication strategies to encourage use. HITECH funding and “meaningful use” requirements may drive availability of patient EHRs, but persuading patients to use them will require some effort.

Telemedicine seems be exploding, both in terms of easing of regulation and in terms of payor coverage, so it is not surprising that there are a plethora of companies making their mark in this space. These include American Well, Cardiocom, HealthSpot, NowClinic, or Virtuwell, to name just a few. These may not provide your personal physician, but they offer physician expertise at your convenience – 24/7, from your house or even mobile device, not restricted to a physician’s hours. That’s got to help improve patient engagement.

The IOM just hosted a workshop on partnering with patients, and one of the conclusions was that physicians and health systems need help in developing those skills, plus they may need additional incentives to engage in the kind of dialogue patient engagement requires (why am I not surprised?). When you think about it, though, relying on physicians, or even nurses, to drive patient engagement doesn’t seem realistic. We can spend time and resources on training them, but we still face the barrier of the projected shortages in both professions (physician, nurse), especially with the baby boomers just starting to crash the Medicare barrier. Primary care providers may just be too scarce, especially in rural and other already underserved areas. Not everyone agrees with these dire forecasts, but the point remains, though: the health professional to patient ratio doesn’t scale well into an era of higher patient engagement.

And maybe it doesn’t need to. Maybe it really is up to us as patients to take responsibility. Fortunately, we still don’t have to go it alone.

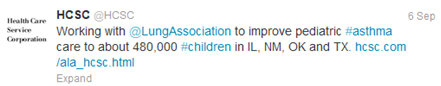

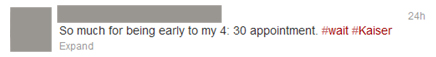

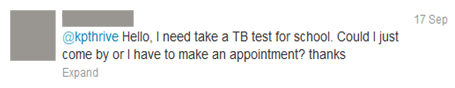

Social media, for example, may not even rely on a provider-patient model. Health care providers are still trying to figure out social media. An infographic by Demi & Cooper advertising/DC Interactive Group suggests that only 26% of hospitals use social media (most commonly Facebook), while over 80% of individuals 18-24, and 45% of those 45-54, would share health information via social media. Meanwhile, Patientslikeme has been breaking new ground for social media use in health care for many years now, using patient-to-patient expertise and experience. We’re only begun to scratch the surface of what patient engagement looks like in a social media world.

Artificial intelligence could be the real game changer in patient engagement. IBM has made a big bet on AI in health care via Watson, and a recent study from Indiana University reaffirms that use of AI has the potential to both improve outcomes and lower costs. Widely available health content on the Internet started this ball rolling, but health care professionals start to look like just another option – a preferred option, to be sure, but no longer the only option – to getting health information, advice, perhaps even diagnoses. And I’ll have to save discussion of robotic surgery for another blog…

We’re already got a mobile stethoscope app, remote monitoring options for conditions like diabetes or blood pressure, medication and other reminder apps, and increasing ability for AI to evaluate and diagnose. Who needs health coaches or even physicians to drive patient engagement? Maybe in the not-too-distant future the model for patient engagement will increasing look like patients simply using their mobile devices: i.e., when Siri marries Watson.

At the end of the day, the person who has to be committed to patient engagement has to be the patient.

Share This Post

Share This Post